To say I was raised on What Not to Wear is an understatement. I lived for that shit. I watched it since the Wayne and Stacy days. The show was a staple of my after-school TV rotation, giving the same reliable emotional ups-and-downs as other TLC fare Trading Spaces or While You Were Out. There was the subterfuge and betrayal as that episode’s contestant learned all their loved ones think they dress so badly they signed them up for a reality show; the humiliation as Stacy tapped her pointy-toed stilettos at their pedestrian clothes; the resistance to the Ann Taylor-adjacent mannekins Stacy and Clinton proposed to the contestant as their new, more “flattering” wardobe; and finally acceptance that yes, maybe this sweater with a faux button-up shirt underneath is the answer to not just a better closet, but a better life. And then joy and relief as they trotted out in front of their friends and family in a brand new $5,000 wardrobe that still looked uncomfortably new and unworn.

The U.S. version of What Not to Wear ran from 2003 until 2013, long after I (and I’m guessing most people) had stopped watching it. Its rule-based, biting but also weirdly optimistic approach to fashion didn’t have a place in the 2010s. We were embracing body positivity, inclusivity, by then. Prescriptive makeover shows, like the original Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, which ran from 2003 to 2007, were no longer reality TV bread and butter as we moved to the proto-influencer aspirational fare of Keeping Up With the Kardashians and The Real Housewives franchise.

But now, What Not to Wear has undergone its own makeover for the 2024 audience: Stacy and Clinton will return as hosts for the Amazon Prime-produced makeover show Wear Whatever The F You Want. As the name implies, they will throw out the rule book and give participants more inclusive tools to dressing to express themselves. Or at least, that’s the idea.

“The world has changed a lot since the run of What Not to Wear, and, thankfully, so have we. These days, we have zero interest in telling people what to do, based on society’s norms—because there are no more norms!” Clinton and Stacy stated in a press release. “However, style is still an important form of communication, and we’re excited to show new clients how to align their personal messaging with their life goals. It’s time to celebrate individual style, not prescribe it.”

Clinton and Stacy are right that the world has changed since their time on TLC. But the original ethos of What Not to Wear, i.e., if you just follow [xyz style rule] then everything will be fine, is still very much alive and well in 2024. And fashion rules are perhaps more relevant than ever on certain corners of the internet, even if no one is giving out $5,000 to wayward fashion souls to follow them. Much as some stylists like Clinton and Stacy want to encourage us to reject norms, many are asking for the opposite: just tell me if I can wear this shirt.

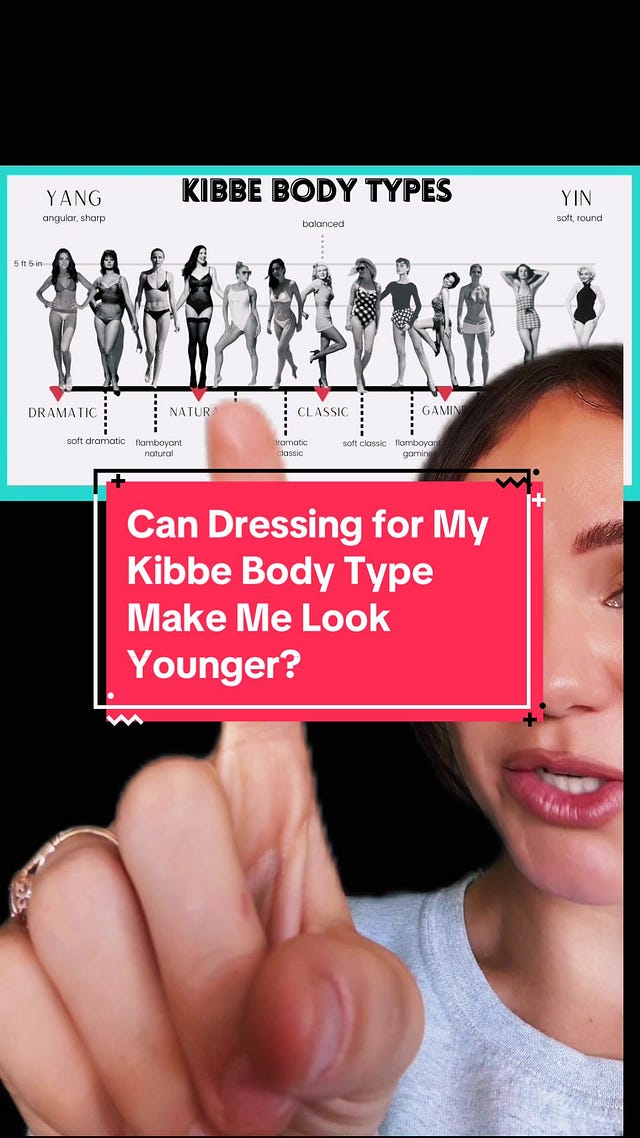

Rule-based fashion guidelines have had a resurgence on social media in the 2020s, bolstered by all ages but especially Gen Zers looking for answers in a chaotic fashion landscape. Take stylist and internet enigma David Kibbe; his personal guide to dressing based on a labyrinth of image archetypes named things like theatrical romantic and flamboyant natural, first published in the 1980s and seemingly not updated since, has had such a resurgance on social media forums like Reddit and YouTube that he was profiled in the New York Times (I’d covered the Kibbe subculture for the now defunct Mel magazine a year prior, RIP). Seasonal color theory, based off of 1970s and 1980s books like Color Me Beautiful and Color Me a Season is all the rage on TikTok as Gen Zers seek to learn if they’re a soft autumn or a true spring. And new style gurus have come up with guidelines and followers all their own, like Rita’s Four Essence System or Merriam Style.

What the original version of Clinton and Stacy’s What Not to Wear, as well as proponents of Kibbe or seasonal color theory, understood is that getting dressed is a fraught experience. In an ideal world, we would be guided solely by our internal style compass, able to choose what to wear based on how we wish to express ourselves rather than what’s “flattering.” But even though 2000s-era magazine style guides that divided body shapes into inanimate objects like banana, apple, and pear are well out of fashion, many of us still want some objective answer to the subjective question: what looks good on me? And “good” and “flattering” still, to many, mean slimmer, younger, more conventionally beautiful.

When I was reporting on style philosophies like Kibbe and seasonal color theory, one theme that came up often from proponents was a kind of relief of finally finding what worked for you. Suddenly there were simple guideposts on what to try amongst a sea of endless options and constantly churning trend cycles. For some proponents of those systems, they offered a kind of antidote to overconsumption, a peace in knowing how to shop for your own needs rather than to chase the trend cycle. And like the original What Not to Wear, there is a kind of pragmatic acceptance that not all of us are fashionistas with an inherent sense of what “works” and what doesn’t. In a time in which no one will tell you outright what works on your banana or apple-shaped body, those rules can seem even more comforting.

The language around fashion “rules” has evolved from the early 2000s; Stacy and Clinton often spoke of “elongating” silhouettes in a sort of thinly veiled fatphobia that I doubt we will see on their new show. But even though there is no longer such an explicit mandate to look as thin as possible, we haven’t shaken those hierarchies of body types altogether. We’ve tried to move on to more inclusive body ideals, but it’s still near impossible to speak of body types — particularly female body types — in a neutral way. What looks “good” simply isn’t a neutral endeavour.

Much as the Kibbe gospel preaches self-love and acceptance, terms like “width,” which appears frequently in the Kibbe language in relation to natural types, still carry negative connotations, while “delicate” language makes types like theatrical romantic more seem more feminine, and subsequently more desirable to a mostly heteronormative audience. And seasonal color analyses still often feature predominantly white faces, without taking into consideration the nuances in features and coloring in deeper skin tones.

Could we stop saying words like "fridge" when referring to Natural myths/stereotypes?

byu/Enthu-Beaver inKibbe

What Stacy and Clinton did effectively communicate in the original WNTW was that our clothes do not exist in a vaccuum; style is its own form of communication, and how we dress is always communicating something, whether we like it or not. That often meant telling sloppily dressed contestants that their wardrobes told the world they didn’t value themselves, and so why should the world value them? We could debate all day about the moral ickiness of that philosophy but there is truth to it. And what many style rules that focus on “flattering” above all else fail to grasp is how our clothing and fashion choices are equally about communicating a cultural narrative or context. Whether we mean to or not, we are always telling the world who we are with our clothing.

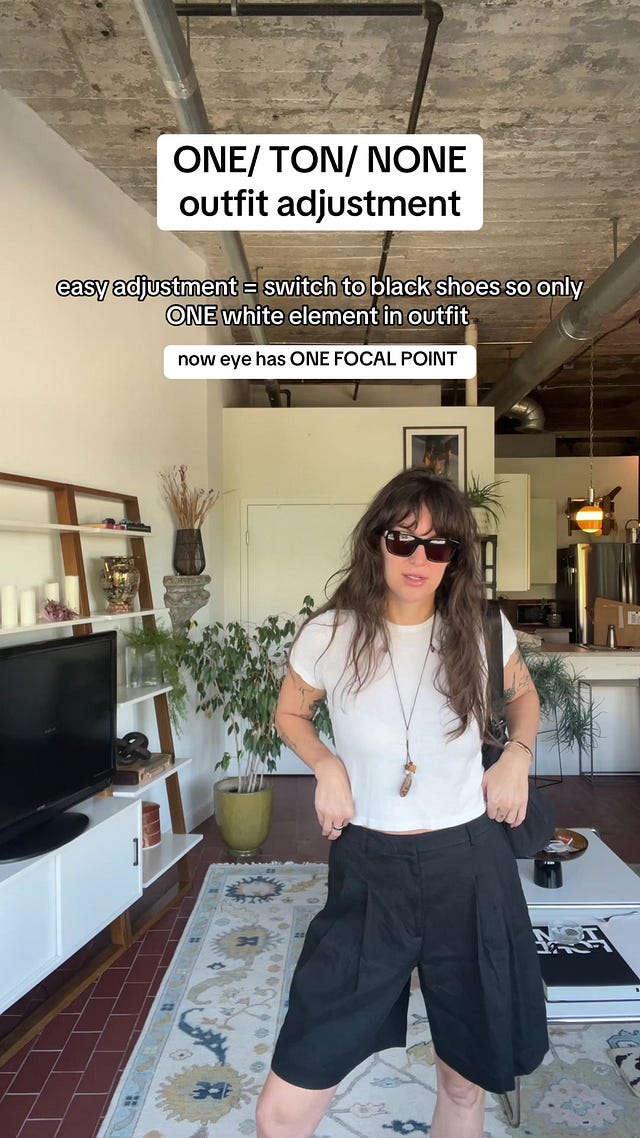

There are contemporary style rules that try to break out of what is “flattering,” however. Anna Baldwin, an Atlanta-based advertising exec and Tibi enthusiast, is constantly on my TikTok for you page showcasing her style rules. She walks her audience through guideposts like “one/ton/none” when it comes to color, or “big/slim/skin” when it comes to silhouette. She talks more about how the clothes work together and what feeling she is trying to go for, rather than how the outfit looks on her body in particular.

But Baldwin’s style guidelines are far from foolproof, as they still require the user to do much of the work on their own. You must have your own ideas about color and shape and what you like and don’t like. You ultimately have to go out and pick the individual items of clothing yourself, guided by your own taste.

Often, the failure of many original What Not to Wear makeovers was that they took someone with some degree of personal style — albeit a lack of budget or resources to execute that style — and beat that nugget of point-of-view out of them until they looked more polished, but at the expense of any quirk or personality. This is not so much the fault of Stacy or Clinton personally — I do think they did their best, and I think Stacy in particular clearly has her own finely honed sense of style. But it is perhaps a reflection of the reality that teaching someone else how to dress “well” is almost impossible. But damn if it isn’t tempting to try.